Whilst on my travels in York recently (I do leave Cumbria occasionally) I came across this in the Yorkshire Museum.

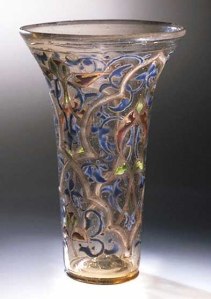

The Ormside Bowl was found near St James’ Church in the village of Great Ormside in the Eden Valley in the early 1800s. The circumstances of its discovery aren’t clear; it was long assumed it was found buried, but at least one archaeologist1 has suggested that the condition is too good for that to be the case.

It’s really two bowls fastened together. The outside, the oldest part, is made of silver-gilt and dates to the mid 8th century. The inner part Continue reading

y that they think there’s a connection to King Arthur, and that he’s buried at the Giant’s Grave in Penrith (although the evidence leans towards it being the grave of a different Owain1).

y that they think there’s a connection to King Arthur, and that he’s buried at the Giant’s Grave in Penrith (although the evidence leans towards it being the grave of a different Owain1).

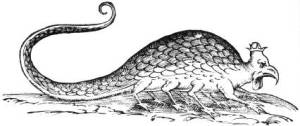

optional wings. They killed their victims with poisonous venom or by turning them to stone with a glance.

optional wings. They killed their victims with poisonous venom or by turning them to stone with a glance.