Today I present for your delectation three lovely ‘celtic’ bronze brooches, all of which were unearthed at Brough in eastern Cumbria. They are officially ‘romano-British’1 which means that they date to the four hundred years after the roman invasion, but archaeology suggests that they are the products of a bronze workshop on this site in the 2nd century CE2.

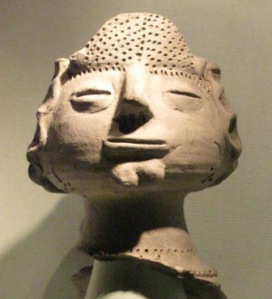

Triskele brooch from Brough. Copyright British Museum

Brough is a signficant historical and archaeological site. When we look at a modern map, we assume that the main route into Cumbria has always been the M6 but this isn’t the case. The north-south route, despite its roman road (the A6, more or less), was not as significant as you might think. When the railway line was cut parallel to the A6 in the 1870s, engineers had to make 14 tunnels and 22 viaducts just to get the gradient under 1 in 100 and thereby traversable by the latest in high-powered travel at the time, the steam train. The more practical route for centuries –millennia, perhaps – was the Stainmore Pass, or, was we know it, the A66. Continue reading →