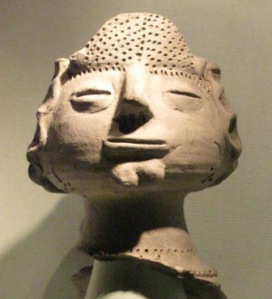

Cocidius altar, Tullie House, Carlisle

Sometimes it’s easy to forget that there were people here before the Romans. But they were here, leaving echoes of their lives and beliefs through place names, 5,800-year-old tools and 2,000-year-old weapons. The natives didn’t write stuff down before the Romans got here, but we soon learned to carve stuff on stones, just as they did. A handful of early inscriptions mention a people called the Carvetii, ‘the deer people’, who appear to have been a sub-group of a large northern tribe called the Brigantes – and we had a number of local gods.

The Romans had an impressively egalitarian approach to the religions they encountered as they travelled the world. They believed the same set of gods was present everywhere but just known by different names. When they came across a native god, they looked in their own pantheon for the Roman equivalent, which is how Lugus – after whom Carlisle is named – came to be seen as a different name for their own god, Mercury. Every native god in turn was partnered with its Roman equivalent and this is how we get to hear about the northern British god, Cocidius.

There are no less than nine carved images and 25 inscribed dedications to Cocidius on Hadrian’s Wall, some from Netherby and Carlisle and others found by Cumberland Quarries (exact site unknown). There are six inscriptions from Bewcastle fort in Cumbria, where he is described as ‘Mars Cocidius’, which means the owner of the altar believed that Cocidius was the native name for the Roman god of war, Mars. Two silver plaques found at Bewcastle show Cocidius wearing a helmet and holding a shield and a club or spear.

The Ravenna Cosmography – a 7th-century summary of all towns that had been in the Roman empire – mentions Fanum Cocidius, which means Cocidius’s Temple. It says that it was between Maia (Bowness-on-Solway) and Brovacum (Brougham). Given this description and the number of inscriptions found, it’s tempting to believe that this site was Bewcastle.

At the eastern end of Hadrian’s wall, Cocidius is linked to forests, and hence to hunting. In an inscription at Ebchester in County Durham, he is ‘Cocidius Vernostonus’ – Cocidius of the alder tree – and at Housesteads Fort and Risingham, he is ‘Sylvanus Cocidius’. Sylvanus was the Roman god of wild forests. An intaglio found at Habitancum Roman Fort on Dere Street at Risingham shows Cocidius surrounded by leafy branches, holding a hare, accompanied by a dog. A further north-eastern image at Yardhope at the tantalisingly-named ‘Holystone Burn’ (the name pre-dates the discovery of the carving in 1980!) shows Cocidius with hat, spear and shield, legs akimbo, arms wide.

Cocidius at Yardhope, Northumberland

There used to be another image, known as ‘Robin of Risingham’, but it was blown up by an 18th-century landowner who was fed up of people visiting it. I find it intriguing to think of people hunting out the carving in this period, and the name is suggestive: Robin Goodfellow is a name from folklore linked to forests (think Robin Hood) and impish creatures (Shakespeare’s Puck). It may be too much to suggest that the 18th-century people knew that the carving represented a pagan deity but they may have thought there was something otherworldly, even magical, about it. A half-size carving based on a drawing of the original was erected in 1983.

As is often the case with Celtic names, the etymology is frustrating. It could derive from ‘cocco’, the Brythonic word for red, or it could be ‘coit’, the root of the modern Welsh word, ‘coed’, which means woods or forest. Supporters of the former interpretation point to rare references to an Irish Gaelic god, Da Coca, ‘the Red God’, suggesting he is just another version of the same deity, in the same way that Carlisle’s Lugus is the Irish Lugh (and the Welsh Lleu). The colour red is readily associated with Mars and war-like qualities (although this is often overstated) and Cocidius is portrayed with a weapon and a shield. Supporters of the forest interpretation point to the inscriptions identifying Cocidius with Sylvanus, the forest god, and the hunting images. To confuse or elucidate matters – take your pick – the alder tree – as in ‘Cocidius Vernostonus’, Cocidius of the alder tree – was well-known for oozing bloody-red sap when freshly cut. Perhaps it’s not so mad to combine the two, and Cocidius in his original Celtic form was a hunter of both men and animals.

Sylvan Men by Albrecht Durer, 1499

And there I would have ended the story of Cocidius, the northern British god, if I hadn’t come across this image, painted in 1499 by Albrecht Durer. These wild men, legs akimbo, arms aloft, carrying a shield and a club, are the very image of Cocidius. They are a conventional medieval Germanic portrayal of woodwoses – a concept known to medieval English as the ‘wodwos’ of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (c. 1390) – and possibly cognate with the medieval Green Man*, an image seen in British cathedrals from the 11th century onwards. Other woodwose-type wild men are found in other European cultures; in Lombardy, they’re known as ‘salvangs’ – wild men derived from the name of Sylvanus.

I don’t know, and suspect that no one knows, whether these deities and wild men are all ultimately the same. Perhaps they all just answer a need felt throughout history to personify a wild, dangerous aspect of nature, which was a threat to man and beast alike. Whatever the case, Cocidius was Cumbria’s very own.

© Diane McIlmoyle 30.01.12

* I should point out that there are two inscriptions to a native god, Viridios – which literally means ‘green man’ – found in Lincolnshire.

You can see an altar dedicated to Cocidius at Tullie House Museum in Carlisle. www.tulliehouse.co.uk

Note added 22.03.12: English Heritage tell me that they are opening a permanent exhibition on Cocidius at Housesteads Roman Fort, near Hexham, opening on 31st March 2012. The site isn’t open all year round so do check before you go. :http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/daysout/properties/housesteads-roman-fort-hadrians-wall/

Note added 01.05.12 There’s a post on the Bewcastle cauldron, a giant Iron Age bronze pot found buried at Bewcastle.