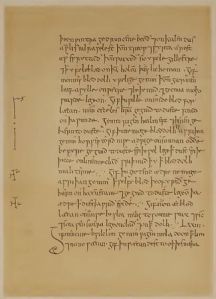

Picture time!

I bet you’re thinking, ‘ooh, that looks a bit like the ring in Lord of the Rings’. Well, you wouldn’t be far wrong. This ring is 9th century and made by anglo-saxons, and JRR Tolkien was an expert in anglo-saxon language and literature. I don’t doubt he knew the Kingmoor Ring very well.

It’s called the Kingmoor Ring because it was found at Greymoor Hill, near Kingmoor, a couple of miles north of Carlisle – locals will know this is now the location of Junction 44 on the M6. As is often the case with these old finds, it was found in a completely unremarkable way. A young man was hammering away at a wonky fence some time in the very early 1800s and came across it in the ground. It was in the possession of the Earl of Aberdeen by 1822 and was passed to the British Museum in 1858.

The Kingmoor Ring is gold, with a diameter of 27mm, which makes me think it must be a man’s ring. There is an inscription on it in runes, permanently blackened with niello so the letters still stand out over 1100 years after it was made (that would have confounded Sauron). Another near-identical ring, known as the Bramham Moor Ring, was found in West Yorkshire in the early 18th century.

I bet you’re waiting for me to tell you that the inscription means something prosaic – perhaps the owner’s name, or a dedication to a family member or a deity? Well, you’d be wrong. To quote the British Museum, ‘various attempts to decipher the inscriptions on these two rings… are not regarded as successful. … the sense is very probably magical’1.

The words have been transcribed from runes as ærkriufltkriuriƥonglæstæpon tol. The ‘ærkriu’ part is believed to be a spell to stop bleeding, which is also found in a 9th-century anglo-saxon medical manuscript known as Bald’s Leechbook. The rest of the phrase isn’t strictly logical but includes words and terms seen in other known charms2. It does include an Irish phrase for ‘stream of blood’ and a reference to alder.

Alder trees feature in other remedies in Bald’s Leechbook but I also recall a reference I discovered when researching Cocidius, the local pre-Roman war god. Cocidius is sometimes described as Cocidius Vernostonus, or ‘cocidius of the alder tree’; it’s not known whether that was making a link between a god of war and ancient forest deities, or, possibly more likely, referencing the blood-red sap of freshly-cut alder wood. The Kingmoor Ring was found within a very few miles of a great many Cocidius inscriptions, which makes me wonder if the alder/blood reference was understood a full millenium before the anglo-saxon chap lost his ring.

Charms to prevent blood loss continued through the centuries. In 17th century Germany, Robert Goclenius the Younger developed a charm which used cupric sulphate, also known as roman vitriol or weaponsalve. The chemical was smeared on the weapon that had caused the injury to cause the wound to close – a remedy for peace time only, it would seem. Weaponsalve soon became popular in Britain, too. In 18th century Cumbria, a different charm to close wounds involved collecting a few drops of spilled blood and using the very same chemical. In this charm, the chemical itself turned into blood as the bleeding stopped.

Wearing a magical ring seems much simpler, doesn’t it?

There is a replica of the Kingmoor Ring at Tullie House Museum in Carlisle.

2. See Anglo Saxon England, vol 27 by Michael Lapidge, Malcolm Golden and Simon Keynes (2007), p292.

Bald’s Leechbook survives in one copy which is kept in the British Library.

My precious!

Noooooo! MY precious! 🙂

This is a fabulous post. I would have never guessed about the spells. Fascinating!

Glad you enjoyed it, Carol! I have to say, I was astonished when I read on the BM’s site that even they say that it was intended for a magical purpose. I double, triple and quadruple-checked that opinion elsewhere, and there’s no doubt that’s the consensus for both this ring and the very similar one from Yorkshire. Mind, if those words appear in that contemporary magical/medical script, how much room is there to disagree? Even without all that, it’s a truly beautiful thing.

Thank you so much for coming over 🙂

Awesome! Alder is my Celtic Regent tree…medieval medicine remedies were always a mix supersticion magic and alchemy…like stop bleeding formulaes which were thought to have sacred powers and posessed by holy people…like this one I have learned from a ceremonial magic book by Trachtenberg “take some of the blood which has been shed, parch it in a pan over the fire until it becomes dry and powdery, and place it on the wound.”

Whether powerful or not …at least this ring had the chance to survive to it’s owner isn’t it? A silent testimony still unveiled for sure….

“Precious” post indeed ♥

It is amazing, isn’t it? I’ve come across several magical formulas to staunch bleeding. I guess before people had machines and people to do things for them, they spent more time with large, sharp blades!

And as you say, it certainly survived its owner! 🙂

Thanks for coming over!

Wow – I’m all tingly now!

Lol! Tingly is good 🙂 Glad you liked it!

Interesting that “weaponsalve” used cupric (copper) sulphate to prevent blood loss, as it’s extremely toxic if it gets into the bloodstream!

Well, there’s a scientist talking 🙂 🙂 🙂

Medieval (and early modern) medicine being what it was, ‘weaponsalve’ wasn’t actually applied to the bleeding body part. Goclenius’s version was applied to the blade/other damaging object that caused the blood loss – which is why I say it must have been a peacetime remedy only, as I can’t see men with a potentially fatal wound chasing the enemy across the battlefield with a bag of blue powder! In the Hawkshead version, a few drops of blood were put on a cloth, then a few drops of ‘weaponsalve’ were put on the blood drops. You then put the cloth under the bleeding person’s armpit (yes, really), and as they stopped bleeding, the ‘weaponsalve’ turned into blood.

It’s all based on the theory of ‘sympathy’, ie you apply the remedy to something connected to, or representing the problem. It was a very widespread view across many nations for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. I haven’t the foggiest why cupric sulphate was the remedy of choice for blood loss, though.

Thanks for coming over 🙂

Absolutely fascinating.

Glad you liked it, Carol 🙂

There’s much debate among certain factions of historical recreationists concerning the traces of copper found on some arrow points. I think that question has been partly answered above. There has also been speculation that copper sulphate was used on fledge bindings to kill pests that may eat the feathers. Personally think that’s tosh because I remember my granddads old copper glue pot having a greeny blue tinge. Some fledge bindings are red, my theory is that some fletchers were using iron, others were using copper glue pots. Interesting that woundsalve may have been used to poison the arrows

That’s very interesting, Mike. I wonder if those bowmen applied the copper compound to protect themselves from arrow shots? Medicine/magic used so much symbolism that I can see them thinking that applying the stuff to their own arrow would protect them from someone else’s. Either that, or they were just using a vicious chemical to kill their enemy in two ways! It’s such a shame they never wrote this stuff down, isn’t it?

Thanks for coming over.

English or Welsh bowmen would plant their arrows in the ground in front of them. After standing in the same place for however long, the poisons accumulated in the soil would have been deadly. Some of those men were also suffering from dysentery. Some arrow heads have been found with what appears a coating of brass too. As a deliberate poison, weaponsalve sounds ideal

It would be interesting to know how long ago bowmen were applying cupric sulphate to their arrows. I wonder if Goclenius developed his anti-wound charm using ‘weaponsalve’ as a result of its pre-existing association with weapons? Chickens, eggs, and all that.

Thank you for helping! 🙂

I wonder, given what you say of the Hawkshead charm, what colour cupric sulphate goes if combined with a very weak acid, such as, say, uric acid which is found in sweat. Might it, any chemists reading, turn red and liquefy? Several of the things you mention here seem to rely on the stuff `becoming’ blood, and assuming that it’s not just the association with weapons (or some odd Eucharistic echo!) such a chemical reaction would make a lot of sense of that idea. I don’t have the chemistry to say if it’s at all plausible though!

Good thought, Jonathan – I’ll consult David (see comment up there somewhere) who *is* a chemist to see if he can find out – he presumbly doesn’t know that already or he’d have said. I do think, however, that Bowman’s point about cupric sulphate possibly being used in battle could be the key – if it was used to make sure wounds kill, the charm could be to make sure wounds heal; it seems consistent with contemporary logic. I think I need to do some more research into that idea.

Thanks for coming over 🙂

Just letting you know I seem to be able to get on again now. I managed it by the end of last week, but the layout (of yours) was all over the shop – or all in one long column. It looks fine today. 🙂

Thanks, Diane. I didn’t know I was getting random one-column days 😦

Pingback: Heavenfield Round-up 7: June Links « Heavenfield

Pingback: Penrith’s 9th-century Futhark Broock | Esmeralda's Cumbrian History & Folklore

Simple and simultaneously beautiful

I agree wholeheartedly!

Beautiful ring.Tolkien didn’t have far to go for inspiration for his tales did he?The Magic Isles!And quite possibly the magic is still there….. with the land as always.Garry in Kentucky.

I’m with you there, Garry! When I read that we’ve found seven rings of a similar age with similar inscriptions, it was impossible not to think of Tolkien. He must have known about them, with his background. And okay, I know that’s only the seven rings of the dwarves, but hey! – it’s a start 🙂

It’s always lovely to see that magical things were so closely interwoven in people’s lives in the past. It does make the world feel special, and that’s what this blog is all about. Thanks for coming over and do come again!

If the diameter given in the article is accurate, this would make a ~ size 18 ring. So, it was probably meant for a thumb of a large man.

If the ring is about 7mm across and 2.5mm thick, it would weigh ~ 28.51g (assuming green gold is nearly identical to the original electrum). Who wants a reproduction done? 🙂

Yes, Nick, the diameter is accurate – I saw the replica recently at Tullie House Museum in Carlisle and it is a conspicuously large, heavy ring. Someone had vast fingers!

Sadly, like all Tullie House’s ‘famous’ pieces (the Embleton Sword, Mallerstang Hoard, etc) it’s not labelled to you have to know what you’re looking for, but it’s in the Viking (?) section.

Thanks for coming over!

Now that’s a thing of beauty. The only ring I have ever seen that has immediately muttered quietly to me about getting a copy made (albeit in a less hideously expensive metal).

I see you mention seven of these. So we have Kingmoor, Bramham Moor, and?…

…five other names without grand titles! Intriguingly, one is apparently made of a blue stone. I’d especially like to see that.

Thanks for coming over! 🙂

No problem. Didn’t come far, I’m only at t’southern end of the UK 🙂

Bluestone? Hmmm, that would be something to see, although I’m taken my this one. Are there links to piccies about? Or put up the names of the other five rings and I’ll pass some time having a hunt about t’net. Strange writer is curious 😀

While I’m pondering this piece, I have to say that I am increasingly drawn to the thought of it being a staff ring, something to go about a traveller’s stave rather than being a piece of personal jewellery. A charm for protection upon the journey.

Hi there – I’m not being obtuse! – the other five are in less good nick, don’t have titles, and are not (as far as I know) on display. I believe there’s a picture of the Bramham Moor one on the British Museum’s website (although their database is a pig to navigate). The others in the BM collection don’t have pictures.

The blue stone one is agate, and was probably found near Carlisle, but its provenance (but not date) is unproven thanks to a muddy history over the last 150 years. In the BM (not on display, no pic).

One found near Durham, also in the BM (not on display, no pic).

One found near Edinburgh, in the National Museum of Scotland (but not necessarily on display).

One found in London, in the Museum of London (but not necessarily on display).

One further, found in Northumberland in the 19th century, now lost.

There’s a replica of the Kingmoor Ring in Tullie House Museum in Carlisle. The ring is conspicuously huge but I can imagine what someone has pointed out – it could be a man’s thumb ring, quite easily. Whilst it’s a nice idea for a staff, the charm does appear to be specifically about bleeding and perhaps the man was more at risk of that than the staff, but to be frank, we just don’t know.

It’s all intriging stuff, isn’t it?

Fantastic!

It is, isn’t it? 😀

Reblogged this on My Journey Through Miðgarðr and commented:

Very cool …

Well, thank you. ’tis pretty good, eh? 😀